TigerDoc

| Favorite team: | LSU |

| Location: | Texas |

| Biography: | |

| Interests: | |

| Occupation: | |

| Number of Posts: | 11629 |

| Registered on: | 4/25/2004 |

| Online Status: | Not Online |

Recent Posts

Message

re: 12 year worldwide meta-analysis study revealed Chemotherapy has a 97% failure rate.

Posted by TigerDoc on 2/16/26 at 1:16 pm to BabysArmHoldingApple

My read is that Flats was riffing on the familiar “buried breakthrough” thread storyline rather than endorsing it, sort of pointing out how these claims tend to cluster (secret cancer cures, miracle carburetors, etc).

That said, your breakdown of patents is useful because it shows why these stories don’t map well onto how innovation processes (be they for carburetors or chemo) actually function. It’s a nice example of how sometimes we’re debating narratives as much as facts.

That said, your breakdown of patents is useful because it shows why these stories don’t map well onto how innovation processes (be they for carburetors or chemo) actually function. It’s a nice example of how sometimes we’re debating narratives as much as facts.

People aren't wrong to intuit that distortions in medical markets exist and they make this intuitive cognitive jump:

If the system has profit distortions --> maybe breakthroughs get hidden.

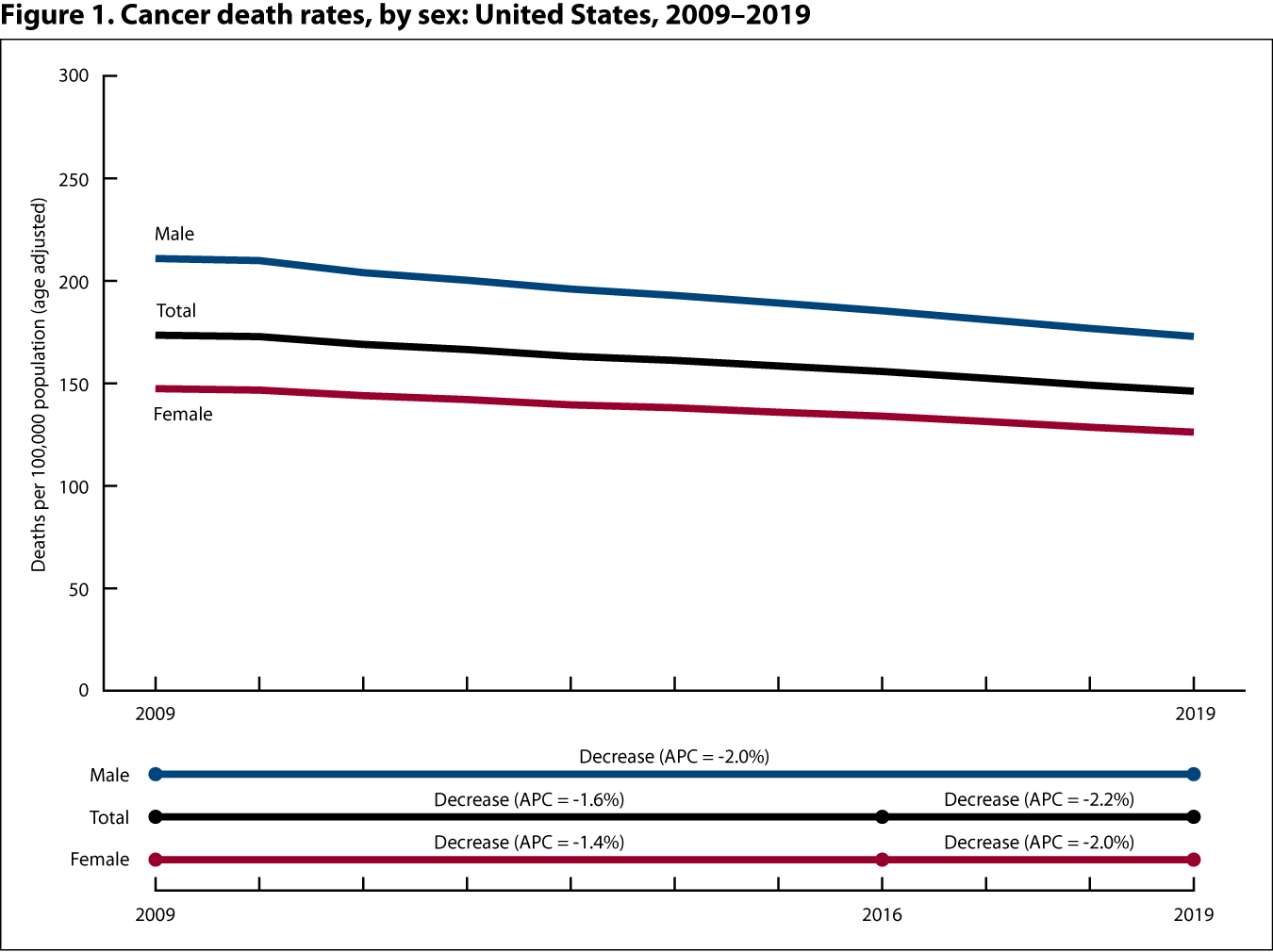

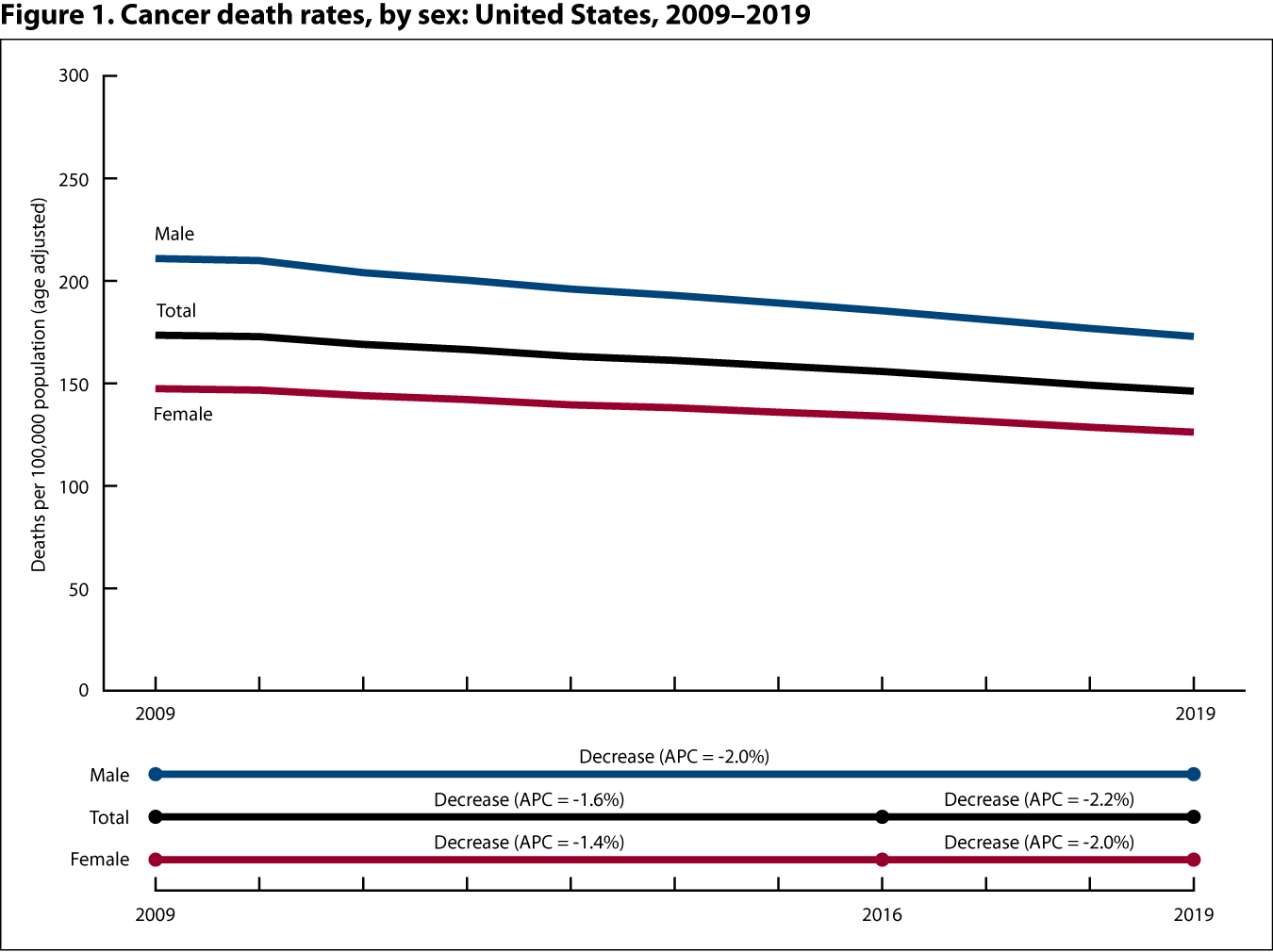

But how distortions actually show up in the world is really quite complex & variable depending on the kind of distortion. E.g., high prices yields access barriers, patent games result in delays in generics, administrative complexity turns into waste, and there is a robust literature for all of it. But where is that for suppressed cures? You can't find it and have to appeal to CT-logic (conspirators naturally conceal evidence) to preserve the possibility, and that's plausible enough to keep people hanging in for it if they're motivated to believe it (and lots of people get shafted by the medical system in many ways and many other industries as well, so there are lots of such people out there). Unfound suppressed cures could of course just still be hidden just waiting to be found, but meanwhile year after year modern medicine is doing this to cancer survival whether those suppressed cures are there or not:

If the system has profit distortions --> maybe breakthroughs get hidden.

But how distortions actually show up in the world is really quite complex & variable depending on the kind of distortion. E.g., high prices yields access barriers, patent games result in delays in generics, administrative complexity turns into waste, and there is a robust literature for all of it. But where is that for suppressed cures? You can't find it and have to appeal to CT-logic (conspirators naturally conceal evidence) to preserve the possibility, and that's plausible enough to keep people hanging in for it if they're motivated to believe it (and lots of people get shafted by the medical system in many ways and many other industries as well, so there are lots of such people out there). Unfound suppressed cures could of course just still be hidden just waiting to be found, but meanwhile year after year modern medicine is doing this to cancer survival whether those suppressed cures are there or not:

re: 12 year worldwide meta-analysis study revealed Chemotherapy has a 97% failure rate.

Posted by TigerDoc on 2/14/26 at 10:22 pm to St Augustine

quote:

This is the dumbest shite. So they let relatively young folks die rather quickly instead of drawing out the treatment for years and actually making more money? Seems like if they “cure” the able bodied people of cancer with these hidden cures they could then profit off of other maladies or relapses, etc.

Yes, if you're looking just at the crass financial motives, living people allow you to generate RVU's and dead people don't. Others have said more or less this & that effective treatments are also bankable (except for extremely rare diseases whose treatments don't have cross-disease treatment potential), but what I should add because it’s easy to miss in conversations like this is that oncologists don’t actually use “cure” as their main benchmark & not because they’re cynical, but because cancer isn’t a single enemy you defeat once. It’s more like a whole ecosystem of diseases that behave differently and change over time.

If you look at medical history, progress against cancer looks less like a movie climax and more like a long engineering project. Mortality has been falling for decades. Treatments that used to be devastating are often more targeted. Some cancers that were once quick death sentences are now managed for years or decades.

It’s a bit like heart disease - nobody talks about how we're either suppressing (or have found) “the cure for heart disease”, but we generally all recognize that fewer people are dying because of incremental advances that quietly accumulated, so slowly that you mostly didn't notice it happening.

There’s something almost tragicomic about it - there is no dramatic moment where someone announces victory, just thousands of clinicians and researchers modestly nudging survival curves year after year while most of the public understandably wishes for a clean breakthrough.

The real story isn’t suppression. It’s slow progress that doesn’t make headlines because it arrives a few percentage points at a time. That leaves things open for grift/ghoulposting however (also tragicomic :lol:).

re: Cenk Uygur (Young Turks) Now Rejects Official 9/11 Narrative

Posted by TigerDoc on 2/14/26 at 11:10 am to the808bass

Yes, I agree. The situation around TPUSA and the speculation circulating after Kirk’s death seems to be a good example because you can see how quickly suspicion can turn inward even within communities that otherwise share a lot of alignment. When trust gets low, groups start to struggle to draw lines between legitimate questions and narratives and trust among allies starts eroding. Another example is Jim Stewartson and his "BlueAnon" coterie, when he started saying wacky things like QAnon is a Russian-created op. It makes me wonder what about our current media/social-media environment just makes these spirals easier to fall into.

re: Cenk Uygur (Young Turks) Now Rejects Official 9/11 Narrative

Posted by TigerDoc on 2/14/26 at 10:25 am to the808bass

thanks. Once the background level of trust drops, it’s surprisingly easy for even smart people to start connecting dots differently than they would have before. It obviously gets more complex than that when there are things like audience incentives, but that's a piece of it, as I see it, and it's probably good to keep separating “something feels off” from “this specific explanation is supported”.

yeah - the conspiracy of the algorithm - there's an illuminati to believe in. :lol:

re: Cenk Uygur (Young Turks) Now Rejects Official 9/11 Narrative

Posted by TigerDoc on 2/14/26 at 8:20 am to SallysHuman

I think what you’re describing, that sense of “it’s everywhere, across domains, all at once”, is something a lot of people have felt over the past decade. When trust takes repeated hits, it can start to feel less like evaluating individual claims and more like living in a general atmosphere of suspicion. In that environment the mind naturally starts linking very different events together and revisiting old ones through the same lens. Sometimes that surfaces real problems & sometimes it can also make unrelated things feel like part of a single pattern even when they may not be.

Probably worth keeping an eye on that distinction. Otherwise it’s easy for the feeling of “something’s off everywhere” to do more of the reasoning than the evidence itself.

That’s partly why I find Uygur’s turn interesting. When someone’s trust collapses publicly, especially someone with a large audience, there’s also a risk of audience feedback amplifying that shift. The more distrust resonates, the more the most distrust-affirming interpretations get rewarded. That dynamic can push almost anyone further than the underlying evidence alone might justify. And then their views feed back to their audience and you can see how it might snowball. In dramatic examples, it can end up in utter epistemic collapse (e.g. Candace Owen).

Probably worth keeping an eye on that distinction. Otherwise it’s easy for the feeling of “something’s off everywhere” to do more of the reasoning than the evidence itself.

That’s partly why I find Uygur’s turn interesting. When someone’s trust collapses publicly, especially someone with a large audience, there’s also a risk of audience feedback amplifying that shift. The more distrust resonates, the more the most distrust-affirming interpretations get rewarded. That dynamic can push almost anyone further than the underlying evidence alone might justify. And then their views feed back to their audience and you can see how it might snowball. In dramatic examples, it can end up in utter epistemic collapse (e.g. Candace Owen).

It seems like he went from loss of institutional trust ("the government lies about Epstein" - ok so far), to therefore they were lying about 9/11, grabbed hold of an anomaly, used motivated re-interpretation to pill himself to trutherism. Note that you could pill yourself into believing virtually an CT that opposes an official account via this reasoning chain.

That makes sense to me, honestly. Having a child in the ICU for HUS is the kind of experience that permanently recalibrates what “real risk” feels like, and it’s reasonable that abstract warnings from regulators won’t move the needle much after that. I wonder if part of what we’re all bumping into here is that once you’ve seen a worst-case scenario up close, everything else gets graded on a different curve, e.g. regulators, activists, even RFK himself depending on the decade. How do you decide when a warning clears a bar of sufficient significance for you?

David, his public record as an environmental activist is a mile long.

Are you kidding? He spent decades as a trial lawyer suing polluters and trying to get stricter environmental regulation passed. He believes chemicals can harm you and should be out of rivers, but E. coli is A-ok.

quote:

"You think a guy who ate lollypops out strippers' buttholes is worried about the flu killing him?" - RFK Jr, definitely

Exactly. This isn't just about risk-taking in the context of addiction. He went swimming with his grandkids in a fecally-contaminated creek less than a year ago. His personal experience has taught him that germs just don't cause disease.

re: The Epstein story is like a Rorschach test.

Posted by TigerDoc on 2/12/26 at 5:14 pm to SlowFlowPro

eta: doubles

(a classic MacGuffin)

(a classic MacGuffin)

re: The Epstein story is like a Rorschach test.

Posted by TigerDoc on 2/12/26 at 5:14 pm to SlowFlowPro

re: Moderna says FDA refusing to review application for its first mRNA-based flu shot

Posted by TigerDoc on 2/11/26 at 8:36 pm to NashBamaFan

that discomfort makes sense. When something goes into people’s bodies, it feels like dosage and timing should be “settled facts”, not moving targets.

What’s tricky (& unsatisfying) is that in medicine, especially during a fast-moving outbreak, some of the most important safety refinements only become visible after very large numbers of people are exposed. That doesn’t mean nobody knew anything beforehand. It means some risks are too rare or too context-dependent to show up until scale forces them into view.

The part that matters ethically is what happens after those signals appear. In this case, spacing doses further apart turned out to reduce risk and recommendations changed accordingly. That’s not evidence that “nobody knew what they were doing”. It’s evidence that the system was willing to revise course instead of pretending early assumptions were sacred.

I get that that still leaves a bad taste. Acting under uncertainty always means some people bear costs we wish they hadn’t. The alternative, though, would have been freezing decisions until perfect knowledge existed, which in a pandemic would have meant a very different set of harms, just less visible ones.

What’s tricky (& unsatisfying) is that in medicine, especially during a fast-moving outbreak, some of the most important safety refinements only become visible after very large numbers of people are exposed. That doesn’t mean nobody knew anything beforehand. It means some risks are too rare or too context-dependent to show up until scale forces them into view.

The part that matters ethically is what happens after those signals appear. In this case, spacing doses further apart turned out to reduce risk and recommendations changed accordingly. That’s not evidence that “nobody knew what they were doing”. It’s evidence that the system was willing to revise course instead of pretending early assumptions were sacred.

I get that that still leaves a bad taste. Acting under uncertainty always means some people bear costs we wish they hadn’t. The alternative, though, would have been freezing decisions until perfect knowledge existed, which in a pandemic would have meant a very different set of harms, just less visible ones.

quote:

The flu shot has missed more years than not lately which means the current process ain’t good enough... On a political message board where 90% of the posters don’t know the difference between an antigen and an ant hill?

Good point. You need a public framework that laypeople could look to (and honestly would be helpful for professionals reading & commenting too) for guidance on what kind of evidence would actually settle the question. For me, a strong comparison would need more than isolated efficacy numbers or mechanistic arguments, it would require convergence across multiple lines of evidence, especially head-to-head clinical outcomes, durability of protection, harm profiles, and whether the immunology predicts what we see clinically. If y'all could point to those, then you could make some progress (maybe :lol:)

ETA: this is ideal case. Obviously, you could make some headway short of this, but less definitively. mRNA tech is new enough that these comparisons aren't available across a variety of diseases, so it won't be definitive, but it shouldn't need to be. If it's at least (1) comparable w/r/t efficacy and risks and also simultaneously (2) faster (of this latter one there is no doubt), then the edge goes to mRNA (controlling for cost of course, so yeah, there's a lot of variables to judge).

I agree that it's a really promising technology for both seasonal vaccines and promising for cancer and even HIV. One thing you might highlight for skeptics is how other major public funders (EU, Singapore investment pools, CEPI, multinational alliances, likely China eventually) continue to invest in this technology and eventually we'll get a chance to decide to license it from them if it bears out and we continue to be allergic to trust Moderna/Pfizer.

quote:

A flu vaccine or booster that covered subclad K would likely have kept them from getting pneumonia. The speed of production of current flu vaccines does not allow for that to happen. By the time a booster for the predominant variant was produced flu season would be over. The greater speed of production for mRNA vaccines would make producing a midseason booster to cover the predominant variant theoretically possible.

This is plausible and if it worked would be very useful, but isn't how Prasad is thinking. He wants to RCT more & more and that'll end up slowing down approvals and they're also going to be favoring presumably the older, slower platforms unless there's some equally fast platform to mRNA that I don't know about, so faster vaccine tech doesn't seem in the offing anytime soon.

quote:

it was obvious the vaccine was marketed and pushed in the wrong way

Good article and good point. It’s not about eliminating all infections. It’s about shifting the odds away from the worst outcomes.

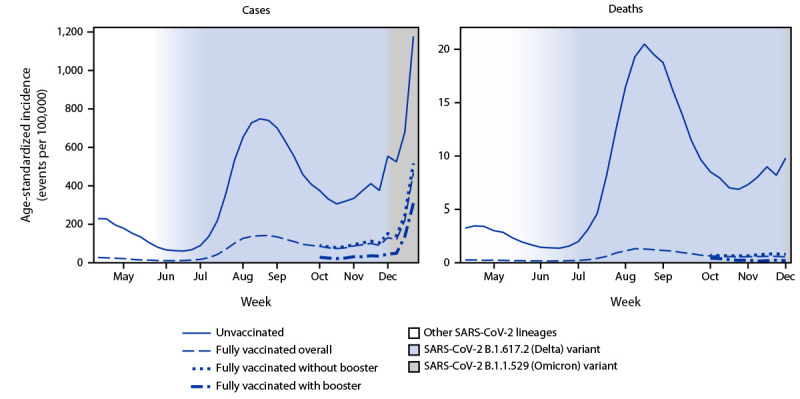

This is crucial because given we've been raised in an era of eradication, people today expect perfect prevention, not risk reduction. The public language around vaccines (especially early messaging) underplayed that distinction. When people do get infected after vaccination (as shown by all lines rising during Omicron) it reinforces the belief that “vaccines don’t work” (or even making people vulnerable to adopting the wacky "it's not a vaccine" idea), unless you carefully frame what “working” really means. You see in the right graph that deaths stay low in the vaccinated group. The vaccines kept people out of the morgue even as they still got sick.

Some vaccines erase a disease from daily life. Others keep a dangerous disease from overwhelming society. COVID vaccines were the second kind. This gets forgotten because most of us have been living in an era where we've had a lot of success eradicating communicable diseases, which is great if you can do it, but vaccines were successful long before this by acting like fire-breaks do, limiting damage, but not eradicating disease. That's valuable too, and the COVID vaccine was like that, and had it been communicated like that, there would be less backlash and resentment today.

Quite right about the danger you’re pointing at. History goes wrong when narrative hardens first and evidence is made to conform to it rather than discipline it.

What’s worth noticing, though, is that this doesn’t usually happen because people reject facts outright. It happens because narratives serve functions - identity, meaning, cohesion - that facts alone don’t provide (I've banged my head arguing facts against narratives long enough here to have learned it the hard way). When those functions dominate, myth can quietly replace inquiry.

Founding legends can oversimplify messy origins & histories can be told as if outcomes were inevitable rather than contingent (or other like oversimplifications), but the problem wasn’t having a narrative (narratives are inevitable). it was forgetting that the narrative was a tool, not the territory. This can happen with abolition history, civil rights history, or any other and you're right to discipline it. What practices, in your experience studying history, best prevent that slide from interpretation into myth?

What’s worth noticing, though, is that this doesn’t usually happen because people reject facts outright. It happens because narratives serve functions - identity, meaning, cohesion - that facts alone don’t provide (I've banged my head arguing facts against narratives long enough here to have learned it the hard way). When those functions dominate, myth can quietly replace inquiry.

Founding legends can oversimplify messy origins & histories can be told as if outcomes were inevitable rather than contingent (or other like oversimplifications), but the problem wasn’t having a narrative (narratives are inevitable). it was forgetting that the narrative was a tool, not the territory. This can happen with abolition history, civil rights history, or any other and you're right to discipline it. What practices, in your experience studying history, best prevent that slide from interpretation into myth?

Popular

0

0